A Fatherless Father’s Day

A Fatherless Father’s Day

I caught my father sneaking out of the house early one spring morning on his way to the hospital. That image of him standing in our upstairs hallway is forever emblazoned on my brain; from the jacket he wore to our whispered conversation, the memory is as vivid for me today as if it happened only yesterday. Dad thought that he was simply experiencing the repercussions from a recent car accident, and he promised that he would return before I knew it. Instead, it was the last time that I ever saw him. He died in the hospital from cancer six months later. I was only six years old.

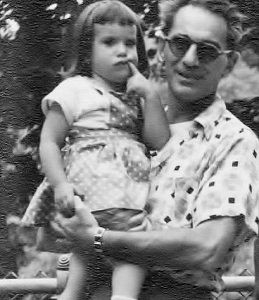

All I had to hold onto was a little girl’s image of that bigger-than-life hero, the first man who ever loved me. Even as a child, I must have appreciated the magic of objects—a foreshadowing of my professional life as a museum educator and curator. I knew that even the most ordinary item is capable of conjuring up the memory of a lost loved one, so as far back as I can remember, I hoarded any tangible proof of my father’s earthly existence—a few photos purloined from Mom’s photo album, Dad’s army dog tags, and later, his gold pocket watch. As meaningful as these mementos were, however, sadly, they could never be enough. When you lose a parent at such an early age, you’re left with a gaping hole in your heart; there is a persistent, visceral reminder that something is gone that can’t ever be replaced. That gouged-out emptiness only grew stronger as each major milestone in my life came and went with my father’s conspicuous absence— especially my wedding day. When we’re little girls, we believe that we’re supposed to marry our fathers, but as childhood fades, we know that their job is to walk us down the aisle and give us away to somebody else. Unfortunately, my father wasn’t there to marry me or give me away.

What is it about that mysterious relationship between daddies and daughters? Can that special bond ever be broken by distance or death? Will we always be their little princesses no matter how old we get? I once read that a daughter may outgrow her father’s lap, but she can never outgrow the place in her father’s heart. There’s no denying that our fathers are our first loves, and that our first taste of the love and security that is to be found in a man’s arms comes from the times spent in our fathers’ arms. Their eyes are the mirrors in which we first learn to see ourselves as beautiful and as capable of giving and receiving love. When they rain love and attention upon our mothers, we are taught to expect the same from all the other men in our lives. Our fathers are there to wipe away the tears caused by scraped knees and, later, from broken hearts. When they run alongside our two-wheelers for the very first time, they know when to hold on and just when to let us go. When they scare away the monsters under our beds and the demons in our nightmares, it allows us to be fearless to dream. Before we can learn how to stand on our own two feet, we must first learn to dance by standing on theirs.

I can’t help but wonder. Has growing up without a father nurtured these impressions of the father-daughter relationship? Are these notions simply fantasies courtesy of Hollywood and Hallmark? Would reality have lived up to the narrative that I’ve created for myself had Dad lived longer? I can never be certain, but that narrative is all I have.

What is certain is that when you grow up without a father, knowledge of your family legacy remains incomplete. In a way, half of you is missing; you’re always left wondering what characteristics you inherited from him. When I look in the mirror, the physical traits are clear. I have photographs to remind me that I am indeed my father’s daughter, but which qualities inside of me echo his dreams, his personality, or his heart?

I expected these unanswered questions to taunt me for the rest of my life, but then, shortly before my mother passed away, she gave me an extraordinary gift—a box of all the love letters Dad had written to her during World War II. Since the day that my father died, she had rarely spoken about him, and I had quickly learned not to ask any questions. It’s as if we both danced around my father’s death by not giving it words, in hopes that it might go away. I suppose this surprise offering of letters was my mother’s way of making up for that deafening silence.

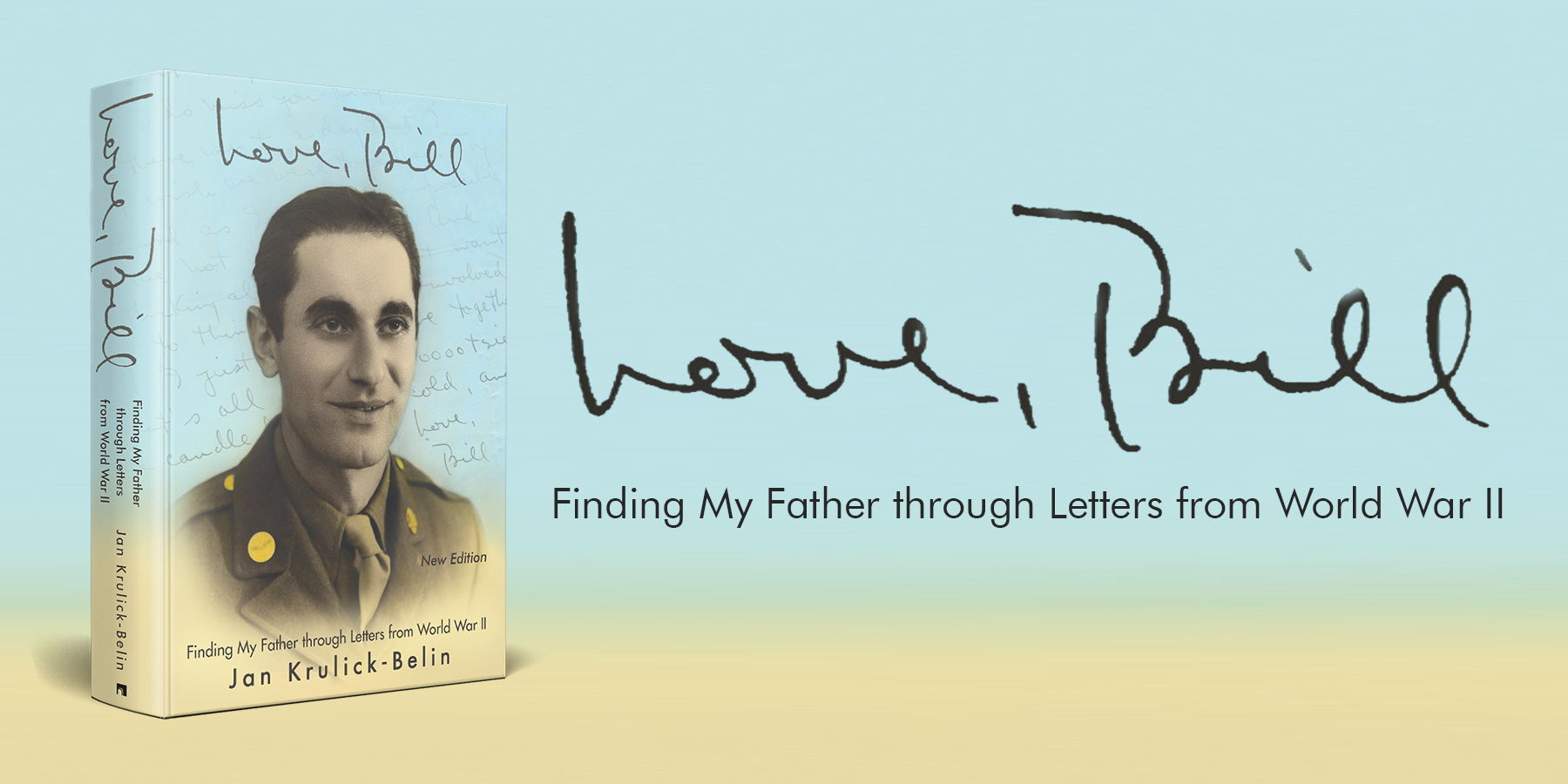

It took me another five years to build up the courage to open that box; I was afraid to have my childhood image of my father dashed. Once I did open the box, however, the letters led me on an amazing emotional, physical, and spiritual journey that resulted in my book, “Love, Bill: Finding My Father through Letters from World War II.”

How many of us have the opportunity to get to know our parents through their most intimate correspondence? At first, I felt like an intruder, even though it had been my mother’s intention for me to read those letters. As it turned out, they helped me find the father I had thought was lost to me forever—lost then found. The hazy memory of the man was finally made flesh. The voice I had forgotten so long ago returned, as each word and emotion jumped off the written page and filled out the form of a good and gentle man. He was a gifted writer who found the beauty in words, art, music, and even an African sunset. His capacity to give love and friendship was limitless, surpassed only by the love and friendship bestowed upon him by others.

My father’s deep conviction that it was his duty to protect the Jewish race from the Nazi menace led him to enlist at the age of thirty-two. The realization of that sacrifice hit me—I was the proud daughter of a member of the Greatest Generation. Discovering his dream to own a bookstore was no longer a secret to me. The unbridled love he expressed for my mother was indeed the stuff of fairy tales. And all these years later, those love letters to my mother became love letters to me as well.

The letters eventually led me to Morocco, where Dad had been stationed during the war. It was there that an unplanned visit with our guide’s friend helped me find the answers that I had been looking for. Completely unfamiliar with my story and the reason for my trip, he explained to me how a father can live on in three ways: first, through his children; second, through his wealth—not just monetary wealth; and finally, through the good deeds he does in his community. He continued to explain how a father knows deep in his heart which of his children will be the one to carry on for him, and how it was up to the child to recognize that within himself.

Since inheriting the letters, I had kept wondering why I was the one of my father’s three children to make this journey. With that one miraculous chance meeting, however, I realized that Dad had known I was the one destined to make this pilgrimage of the heart—that our lives and stories were inextricably linked. My father had given me the responsibility to continue his story and to be the writer he never had the chance to become. And both my parents knew that I was the child who desperately needed to fill in the lifelong void that they had both unintentionally created—one by dying, and the other by keeping her grief-filled secrets all to herself. In the end, my greatest revelation was that my father had never really left me, that I just had to look for him in different places, and would be able to hear his voice within myself.

So, this Father’s Day will come and go for me just as it has for the past sixty years. There will be no backyard barbecue or carefully wrapped necktie, golf club, or power drill to mark the occasion. But perhaps, I can give him a greater gift. I can offer him the person that I have become—the daughter that I hope he would be proud of. A daughter who, hopefully, inherited even the tiniest fraction of who he was. I can also continue to love him and be grateful for all that he has given to me, then and now. Truthfully, I’m not sure who received the greatest gift this year—I think I’m the lucky one. For once in my life, I understand that the emptiness created by his untimely death will never go away completely. Fortunately, it has now mellowed enough that I am able to say with a less heavy heart, “Happy Father’s Day.”

Bill Krulick and Jan age 2